- Learn metoc manual ag3 with free interactive flashcards. Choose from 4 different sets of metoc manual ag3 flashcards on Quizlet. FLEET OCEANOGRAPHIC AND ACOUSTIC REFERENCE MANUAL CH. 3 - Background Noise. Frequency range of ambient noise.

- NAVSEA OP-3347, United States Navy Ordnance Safety Precautions j The Bluejackets’ Manual k COMNAVSURFORINST 4790.9. Fleet Oceanographic and Acoustic Reference Manual 108.1 Explain the following terms as they pertain to Combat System missions: ref.

Aerographer's Mate 1 & C for the U.S. Forecasting information for a wide variety of topics.

The James Greer itself had an impressive array of equipment to hunt for undersea threats.

A hull sonar, a multifunction towed array, as well as variable-depth sonar that could dip below the various thermal layers submarines use to hide. All systems were currently configured to passive so the James Greer did not give away its location to the enemy, but since the Romeos were using active sonar, there was little doubt the Kilos knew there was a new component to the surface warfare hunt for them, and they would react accordingly.

That meant either they would run, they would hide, or they would attack.

Casino One-One made another dip into the ocean, and again the sensor operator on board reported negative contact. The Romeos were getting closer to Russia’s waters off Kaliningrad, and the pilot of Casino One-One suspected the Kilos had bolted for the safety of their territory, but he didn’t let his guard down for a moment. A Kilo lurking below him could possibly hear his rotors, and either descend deeper and run away or surface and attack the Romeo. It was known that Russian Kilos carried SA-14 man-portable air-defense systems, shoulder-fired antiaircraft missiles that could be launched by an operator standing in the conning tower.

The Kilos weren’t just a threat to surface ships. Casino One-One’s captain knew that his aircraft could fall prey to a Russian sub as well.

• • •

Commander Scott Hagen read his latest op orders from Sixth Fleet Command in Naples, and he blew out a long sigh. He’d have to classify the information as part good news, and part bad, but he told himself if nothing else it would light a fire under his butt, and the butts of his crew.

As if they needed more incentive for finding a pair of submarines that might just kill them.

The USS Normandy, a Ticonderoga-class cruiser, and the USS Mustin, an Arleigh Burke–class guided missile destroyer one generation older than the James Greer, were at this moment racing to join up with a Wasp-class amphibious assault ship in the North Sea. Already with the amphibious assault ship were a San Antonio–class amphibious transport dock ship, and a Harpers Ferry–class dock landing ship. The five vessels would form into an amphibious ready group, and then sail together around the Jutland Peninsula, through the Øresund Strait between Denmark and Sweden, and then finally into the Baltic.

It would take them two and a half days to arrive in the waters around Lithuania, and Commander Hagen knew that while the arrival of the big cruiser and the potent guided missile destroyer would be a tremendous help in the approaching fight against Russia’s Baltic Fleet, the fact these two ships would be arriving just ahead of two thousand U.S. Marines on three other ships meant Hagen damn well needed to have these waters safe enough for an amphibious landing by the time the task force arrived.

And to that end he’d called for one of his junior officers. A knock at the door to his stateroom got his attention, and he looked up to see a fresh-faced lieutenant with blond hair and a nervous expression. Hagen had read the man’s file again this afternoon, and he knew the man was thirty, but to Hagen he looked like he could have been sixteen.

Now even the LTs are starting to look like kids, he said to himself. You’re getting old, Scott.

“Come on in, Weps. Take a seat.”

Lieutenant Damon Hart did as directed, sitting on the chair in front of his captain’s desk.

“I saw you in the CIC around midnight. You’ve been working all night?”

“Yes, sir.”

“I’ll keep this brief, and when I’m done with you I want you to get some chow and hit the rack. I need you ready when we get closer to Russian waters.”

“We’re going in after them, sir?”

“Not as of yet. But since they’ve been coming out after the Lithuanians, there’s no reason to think they’re going to stay in their territorial waters when we get close.”

“No, sir. But I can’t believe they’d really want to mess with us. Our torpedoes are better, we have air assets that can take them out at standoff range. I know their diesel boats are hard to find, but if they come out to play, even for just a second, we’ll annihilate them. They know this, so there’s no way they’d do that.”

“I like your optimism, but you need to dispel any reliance on logic here. I’m sure the captains of those Kilos know we have a better weapons platform than they do. But you don’t know what their orders are. For all we know, Moscow is on the horn with those Kilos right now demanding they make an undersea banzai charge right up our gut.”

The lieutenant nodded, chastened. Damon Hart was a graduate of the Navy’s new Naval Surface and Mine Warfighting Development Center, a Top Gun program for surface warfare officers chosen to be the best of the best, who were then given training to hone their skills to an even sharper point. Then they were sent back out into the fleet, with a mission to bring the level of naval combat up all over the Navy.

Hart’s actual job here on the James Greer was as a warfare tactics instructor. It was his job to make certain every surface warfare officer on the ship knew everything he needed to know about every enemy weapon, tactic, and procedure, as well as U.S. Navy doctrine for finding and destroying undersea threats.

The fact Hart had the details down cold did not necessarily mean he understood the psychology of his enemy, and his captain wanted to make sure he was ready for war. War did not always follow conventional wisdom, or even rational behavior.

Hagen said, “Weps, you’re the best-trained USW officer in the fleet and you’re on my ship. I’m going to work you like a damn dog until this is over, and you are going to push everyone here, including me, if necessary, to fight these Russians the right way. Are we clear on that?”

“Yes, sir.”

“Good. Now those Kilos hit all four of those ships during darkness last night. Doesn’t mean they’ll wait till nightfall to come back out, but they are going to be looking for every advantage they can find. If they hit again, it might not be till tonight. So I want you rested.”

A few minutes later Hart ate chow in the officers’ mess. He was tucked into a corner by himself, a half-eaten chicken salad sandwich on his plate and two large paperback books in his lap. On the bottom was his old dog-eared copy of the RP 33, the Fleet Oceanographic and Acoustic Reference Manual, a sort of bible of undersea science from a submarine and antisubmarine warfare practitioner’s perspective. He basically knew the damn thing by heart, but he kept it close by all the time for quick reference.

On top of this was the latest edition of Introduction to Physical Oceanography. As he ate his sandwich he perused this, looking up some salinity equations he might need in this part of the Baltic.

Hart would read for a few hours, doing his best to push every bit of information needed for prosecuting an undersea target in these waters to the ready reserve in his brain. Antisubmarine warfare moves fast, he knew, and seconds counted. If he ran into one of those Kilos tonight, Hart didn’t want to have to pull out a pair of dog-eared books to remind himself what to do.

• • •

The troop transport train infiltration of Russian Spetsnaz forces into Vilnius County was eighteen hours old, and though the results were far short of the Russians’ H-Hour+18 objective for the op, the plan did achieve the desired effect of wreaking havoc on the Lithuanian population. Rumors of battalions of Russians in the capital city were broadcast on radio and television, on social media, and throughout the foreign press.

As was often the case with late-breaking news, the truth was quite different from the reality. By seven a.m. at the airport terminal and tower, Russian troops were overpowered after a firefight with a combined force of ARAS federal counterterror operators and a company of elite military Special Purpose Unit troops. The Russians had better training, as well as solid defensive positions, but the Lithuanians had the advantage in sheer numbers and equipment, as well as massive amounts of tear gas.

Twenty-one of the Russians were killed i

n the three-hour-long battle, compared with forty-five Lithuanians, most in the initial attack and a disastrous counterattack conducted by well-motivated but outclassed airport security staff.

The airport remained closed for most of the day due to damage to the radars on the roof of the terminal as well as the persistent cloud of tear gas that hung in the stairwells of the control tower, but once the Russians lost control of the facility, the Russian troop transports circling to the east over Belarus were forced to return to the airport in Smolensk with their airborne troops.

The Spetsnaz operation to temporarily hold choke points throughout the capital city had fared better than the airport operation. Here, more than forty men reached their objective waypoints, causing pandemonium during the morning rush hour as small-scale gun battles between Russian Alpha Group and Lithuanian police seemed to flare up all over the city.

But here again, the Russian operation fell short of its goals. The unit’s orders had been to spend two hours out in the streets creating chaos, and then melt away to a large wooded park in the north of the city, where a group of Serbian paramilitaries specially trained for the mission would be waiting with stolen vehicles, clothing, medical equipment, and other resupply. The Serbians had been infiltrated a week earlier with tourist visas, and as recently as twelve hours before the Russian military train arrived in the country, the Serbs had sent word that all was ready. But when the twenty-six surviving Russian special-operations troops arrived at their rally point in the parking lot next to the forest, they found only six Serbians in three vehicles, little in the way of supplies, and a story about how their mission had been undone by a police ambush the evening before where a dozen of their ranks had been killed or wounded.

As the remnants of the Russian and Serbian Spetsnaz men tried to exfiltrate the park, they were confronted by a company-sized element of Lithuanian Land Force volunteers, poorly trained and outfitted young men who had only numbers on their side.

In the ensuing bloodbath the combined Spetsnaz unit killed more than fifty men but suffered heavy losses itself. The few surviving Spetsnaz, all Russian, retreated bloody and broken into the park when their ammunition ran out.

71

Lieutenant Colonel Rich Belanger had spent most of his first full day careening around in a light armored vehicle from his attached Light Armored Reconnaissance platoon, checking on all his Marines’ preparations. He stopped at his companies’ command posts to visit with each commander.

The CP of India Company, called “Diesel,” was an old farmhouse with the men dug in out front in the woods. The CP of Kilo Company, “Sledgehammer,” was in the rear in reserve with the tanks, ready to go into the counterattack when ordered. Lima Company, called “Havoc,” was south of the others, in the woods in ambush positions looking out onto the E28, the main east-west highway that conventional wisdom said the Russians would use to drive straight through to Vilnius.

The weapons company, who used the call sign “Vandal,” had their heavy M2 .50-caliber machine guns spread among the three companies and their 120-millimeter and 81-millimeter mortars well to the rear of the battalion, prepared to fire a hail of steel rain over the lines and onto the Russian advance. The Vandal commander, during combat, would move into the Darkhorse combat command center, where he would control all his fires, including air and mortars. Also in the CP, Darkhorse’s intelligence officer had just gotten the satellite comm systems up and running, and was trying to download the latest intelligence from EUCOM.

By early afternoon, Lieutenant Colonel Belanger, whose call sign was “Darkhorse 6,” was confident his battalion was ready for a fight, but his concerns extended far beyond the twelve hundred men under his command. Small sporadic pockets of Lithuanian Land Force troops continued to surge forward, all over the eastern part of the country, without any real direction as far as he could discern from their attached exchange officers.

They moved around from south of Vilnius to halfway up to the Latvian border, and Belanger had been concerned he would be rushed into action only to be slowed down by having to push his way through roads clogged by their aging vehicles still trying to make it to the border regions or, even worse, by civilian refugees fleeing rearward in the face of the Russian advance.

And that was just one of his many burdens today. The USMC colonel in charge of him, the Black Sea Rotational Force commander, had tasked his intelligence officer with a lot of additional collection duties. Among the most pressing was keeping the BSRF regimental headquarters up-to-date with the latest information out of Vilnius.

All morning long and into the afternoon, Belanger’s intel officer passed word to the regiment back in Stuttgart about a force of enemy sappers who had snuck in on one of the cargo trains and set about conducting sabotage operations in the city.

Finally, the intelligence officer called Belanger in his LAV C2 as he was touring the company engagement areas and suggested Lithuanian army reports had begun to coincide with the news reports they’d been watching on the Internet and CNN. Only a few Russian saboteurs remained; they had been flushed out and into the woods north of the city. Their infiltration game in Lithuania appeared to be over.

On television the Lithuanian government displayed a couple dozen Russian prisoners standing outside at the airport. Heads down in defeat, arms zip-tied behind their backs.

Belanger took one look at them and knew they were Alpha Group men, the best Russia had to offer. While most laypeople in Lithuania took their victory over the Russian commando unit as a sign that their nation could take anything the Russians had to dish out, the Marine lieutenant colonel had a more sober take on the news.

The fact the Russians had a hundred Alpha Group men they could sacrifice on what looked to be little more than a suicide mission into the center of Lithuania before the war even kicked off told Belanger that Russia had thousands of different GRU and Interior Ministry Spetsnaz troops to work with on the front lines. Troops he was certain to meet in the next hours or days, because he knew there were a lot more of those black-clad bastards just over the border in front of him.

Word came down through intel channels that some analysts at the Pentagon had identified a stretch of Belarusan border almost seventy-five kilometers long where the Russian army was mustering; this was likely where they would breach the border. Any farther north or south and they would find themselves away from trafficable roads, or too far from Vilnius, their main objective in the country.

Within this expanse there were four main arteries bisecting the border, and while Russian tanks didn’t need to adhere to roads to attack, their truck-bound infantry, their supply, and the Russian heavy artillery would necessarily proceed on one or more of these roads, so it stood to reason the attack would emanate from one of these areas. Without the infantry, artillery, and a steady source of supply, the tanks would have a tough time in the thick forests and broken fields of Lithuania.

This narrowed down the location of the attack even further, Belanger and his intel officer surmised. To the extent Belanger had divided Darkhorse Battalion into three self-sufficient sections and placed them in three distinct locations near the four roads, they were prepared.

One rifle company could not stop a division-strength Russian invasion, of course, but Belanger had to have someone ready to engage the enemy while the intelligence officers checked the satellite data and confirmed this was, in fact, the spearhead of the Russian invasion, so the rest of his forces could maneuver onto the Russian advance.

The call he had been expecting for twelve hours finally came from EUCOM at dusk. Overhead platform surveillance of enemy troops in Belarus indicated a push to the border was under way, and it was happening in two places simultaneously: on the other side of the border from the Lithuanian town of Magunai in the north, and straight along highway E28, which led from Minsk to Vilnius.

Instantly Lieutenant Colonel Belanger knew his battalion would have to fight on two

fronts, fifty kilometers apart. He dreaded it, but he would have to split his forces.

One half of all Lithuania’s meager resistance force was already largely set up at the E28 at the crossing; it was Belarus’s closest point to Vilnius, so the area was already defended by Land Force soldiers with World War II–era 105-millimeter howitzers, a few newer 155-millimeter howitzers from Germany, and dozens of mortars of different sizes. There were thousands of troops already in trenches, and sandbagged emplacements along the roads, but the space was wide-open enough for Russian tanks to use the fields and pastures to make their way toward the capital.

Belanger knew they could mow right over the Lithuanians unless the defenders received a lot of help from Darkhorse.

No, the local defense wasn’t sufficient, but Belanger kept his India Company, along with a platoon from his weapons company and a few tanks and Cobra helicopter gunships, in the south at the predefined locations given to him from the EARLY SENTINEL deployment program. Each antitank missile, each mortar, each heavy machine gun, and each rifle squad was assigned a ten-digit grid and an azimuth of fire. Fighting holes were dug, equipment was moved under cover, and machine-gun and heavy-weapon range cards were drawn up to support integrated defenses.

Kilo and Lima infantry companies, and some heavy guns and antitank rockets and missiles from the weapons company, were ordered north to Magunai, where they were given defensive positions throughout the city and in the nearby farms and forests. Lima was in front, within sight of the Belarusan border, and Kilo stayed to the southwest, ready as Belanger’s counterattack force, or to race all the way down to help India if absolutely necessary.

Belanger’s intel officer identified that the expected northern breach zone for the Russians was virtually undefended by Lithuania, so the Marines would have to do the lion’s share of the work to stop the Russian attack.

Belanger moved his forward command post into a supporting position behind his Lima Company, then ordered forward air controllers, plus a few JTACs—joint terminal attack controllers, scrounged from other units—to be split among all his company’s strong-point defensive locations.

By: Will Spears

Reading Time: 7 Minutes

Today there are five doctrinally recognized operational domains: land, maritime, air, space, and cyberspace. The DOD Dictionary, citing Joint Pub 3-32, defines the maritime domain as the “oceans, seas, bays, estuaries, islands, coastal areas, and the airspace above these, including the littorals.” While it provides definitions for all the recognized domains, it leaves the term domain conspicuously undefined. Dr. Jeffrey Reilly defines domain as a “critical macro maneuver space whose access or control is vital to the freedom of action and superiority required by the mission.” This short commentary will propose that the undersea, those areas of the oceans, seas, bays, estuaries and littorals extending from the surface to the seafloor, is itself a discrete operational domain in accordance with any reasonable definition of the term.

Just as multidomain operations are nothing new, identifying the undersea as a specific domain onto itself is also nothing new. For example, according to its commander, the mission of the U.S. Submarine Force is “to execute the mission of the U.S. Navy in and from the undersea domain.” It isn’t likely that that the Submarine Force is intentionally at odds with joint doctrine in identifying the undersea as a separate domain, but rather that it hasn’t yet become important for various arms of the U.S. military to get on the same page as to what a domain is. As multidomain operations continue to transition from Pentagon buzzwords to modus operandi, minor glitches like the above will be quietly ironed out.

It matters because conceptual accuracy matters. The models we use to represent complex ideas turn into mental shortcuts that, for good or ill, end up shaping our way of seeing things. These views shape discussion and debate, which in turn shape plans and policy. To lump the undersea together with the ocean’s surface and the air above it is to over-generalize to the point of obscurity, pushing the undersea, its opportunities and its vulnerabilities into the periphery of consciousness. Our undersea forces are comfortable in obscurity, but our joint commanders require plans and policy that are developed with full appreciation of all opportunities and vulnerabilities at play.

Why the undersea is different

Skeptics may argue that the maritime domain is an unnecessary hair to split. We don’t, after all, sub-divide land into mountain, jungle, desert, or urban domains. That’s because these are types of terrain, and while they require different training and doctrine to negotiate, they are not fundamentally different spaces of maneuver. The ocean also has terrain— ice, littorals, open ocean, archipelagic waters, or high-traffic straits for example—each requiring its own training and doctrine, each presenting its own challenges. These challenges manifest very differently above or below the ocean’s surface, though. Polar ice, for example, affords a haven for undersea forces while denying access to surface ships. Those same surface ships can maneuver unimpeded through shallow waters that submarines may find challenging or inaccessible.

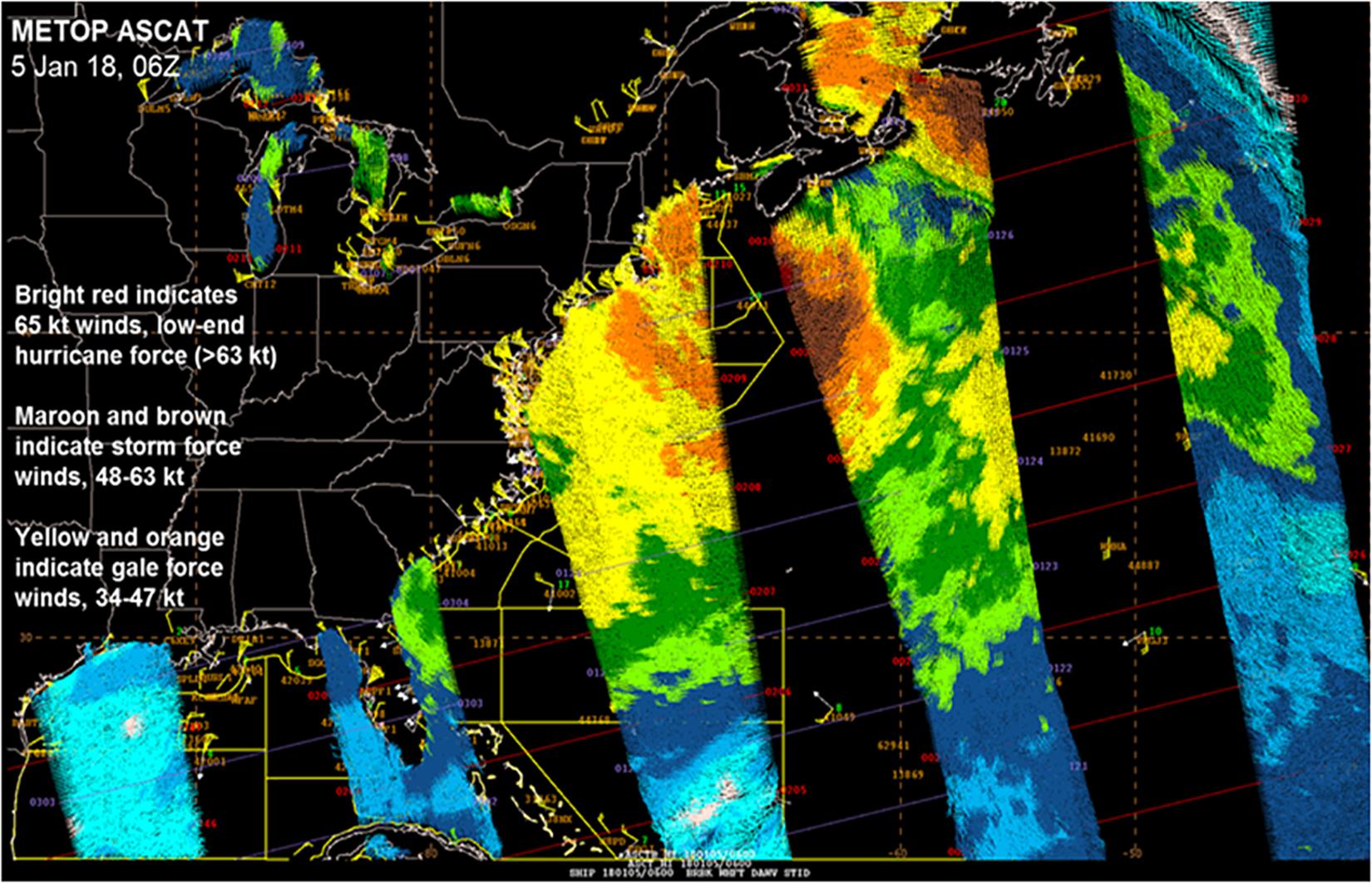

Even in open ocean, the shape and composition of the seafloor matters to undersea forces. Submarines sense their environment through vibrations, which travel much faster in water than in air. Sound travels any direction but straight in water, reflecting or refracting from the surface, seafloor, or thermoclines, and interacting with ocean weather like fronts, eddies or ocean currents. A sloping or mountainous seafloor will have different characteristics than a flat seafloor, and clay will reflect sound differently than rock or sand. These effects converge to produce a variety of phenomena such as sound channels, surface ducting, or convergence zones, all of which are important to understanding the undersea domain.

Radar is not a factor underwater. Visible light barely penetrates the ocean’s surface. Undersea forces minimize communication by necessity, naturally operating with a mission command philosophy that is deeply ingrained in submarine culture. These factors converge to make undersea forces the least vulnerable of any military assets to effects in the electromagnetic spectrum, as well as the least likely to be crippled by an attack on space assets. Unfortunately, these factors also make it hard to communicate with submarines, making coordinated submarine operations a cumbersome task that is often frustrating for addicts of nonstop communications.

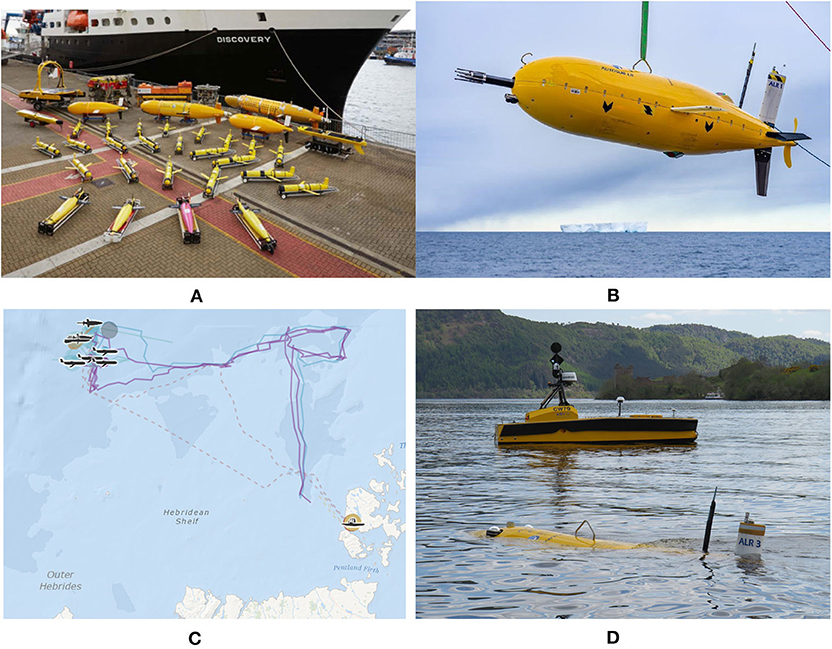

Much like the space domain is closely linked with the air, the undersea domain is closely linked with the surface. Undersea forces must transit the surface domain to access the undersea and must return to the surface for repair and replenishment. Unmanned undersea vehicles are frequently deployed from surface ships, and sea mines are undersea weapons with effects in both domains. Like space, the undersea domain is critical to the information-age economy, with substantial energy assets and an elaborate web of cables supporting international communications. Unlike space, the undersea is home to vast arsenals of very lethal capability, including the sea-based deterrents fielded by every major nuclear weapons power.

Any future contest for command of the sea will hinge upon what happens in the undersea. Neither party may claim to have achieved sea control while either the surface or the undersea remain contested. Likewise, neither party is denied the sea while they can still operate on or under the surface with acceptable levels of risk. For example, continental powers may aspire to deny access by holding naval surface forces at risk with inexpensive land-based missiles. Without a complementary ability to hold undersea forces at risk, access cannot be denied, only contested.

In a rapidly evolving high-end conflict, control of any domain will be constrained in time as well as geography. Operating inside of highly dynamic “windows of superiority” requires rapid-fire decision-making informed by an organic understanding of the opportunities and vulnerabilities presented in every domain. This understanding is better served by a conceptual model that examines the surface and undersea as closely linked but discrete operational domains.

A Problem of Concept

A separate undersea domain does not mesh well with the “every service operates in every domain” narrative that seems to be critical in conceptually separating joint from multidomain. No service other than the Navy has the equipment or expertise to produce effects in or from the undersea domain, nor should they aspire to. This is not a problem of practicality, but one of concept, in that acknowledging a separate undersea domain will require refinement of language in other aspects of multidomain thought. It is not as simple as splitting the maritime domain in two.

Put simply, the five-domain model of land, maritime, air, space, and cyberspace is not well thought out. Rather, it is a baby step toward multidomain thinking, derived from little more than attaching space and cyberspace to the traditional responsibilities of the Army, Navy, and Air Force. The doctrinal definition of maritime as the “oceans, seas, bays, estuaries, islands, coastal areas, and the airspace above these, including the littorals” could be more simply stated as “things the Navy is responsible for.” This is a definition that emerged with an established service in mind and is not sufficiently precise to support future evolution of multidomain thought.

While this commentary is intended to provoke debate rather than to establish any sort of precedents, I offer the following as a point of departure for missing definitions. Instead of an all-encompassing maritime domain, there is a surface domain and an undersea domain. The undersea is defined as those areas of the oceans, seas, bays, estuaries and littorals extending from the surface to the seafloor. The surface is defined as those areas of oceans, seas, bays, estuaries and littorals that are navigable by marine vessels lacking the capability to submerge (i.e. polar ice regions are excluded from the surface domain). Islands and coasts are land, and riverine forces belong to the land domain as well. The air is the air, regardless of whether land or sea is under it.

Conceptual Accuracy Matters

To operators, military theorists debating nebulous concepts can sound a lot like philosophers babbling over semantics, ultimately producing flow charts and Venn diagrams with zero utility to the warfighter. That’s not what the multidomain imperative, or this commentary, is about. Regardless of what conceptual banner the transition falls under, seams in between operational domains are going to become increasingly transparent as a matter of necessity and natural evolution. Clarity of thought and language is a necessary and heretofore untaken first step to ensuring this transition occurs in accordance with a plan. Given the stakes, it isn’t asking too much to expect that it’s done right.

LCDR Will Spears is a U.S. Navy submariner and a student in the Multidomain Operational Strategist concentration at the Air Command and Staff College. He has served aboard multiple attack submarines in the Western Pacific area of responsibility.

The views expressed are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the Department of the Navy, the Submarine Force or any organization of the US government.

Iceberg feature image from http://www.kinyu-z.net. Underwater sound profile image from unclassified publication Fleet Oceanographic and Acoustic Reference Manual. Other images are original.